The Heinkel He 178 was the world’s first turbojet power aircraft and the first practical jet plane. This German aircraft made its debut on August 27, 1939. The first flight of an Italian motorjet engined aircraft was the Caproni Campini N.1 on August 27, 1940.

On the allied side, the British experimental Gloster E.28/39 first took to the air on May 15, 1941 and the Bell XP-59A, with a version of the Whittle engine built by General Electric, flew on October 1, 1942. Soviet efforts focused on the Bereznyak-Isayev BI-1 rocket plane, which first flew on 15 May 1942 and the Yak-7R liquid-fuel rocket booster/twin ramjet aircraft which also flew that year.

As I see it, the possibility of an alternate timeline hinges on the demonstration of the jet for the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (“Reich Aviation Ministry”, RLM), where both Ernst Udet and Erhard Milch watched the He 178 perform, on 1 November 1939. Rather than exhibiting official disinterest the pair are impressed by the jets performance and convince Hermann Göring that further development of jet propelled aircraft should be pursued.

In the end, these early jets would have had very little impact on the outcome of the War. Jet interceptors, in numbers, would have played havoc with the US daylight bombing campaign but it is unlikely that Germany would have been able to produce large numbers of jets due to a lack of strategic resources and propeller driven fighters were already making daylight bombing a difficult proposition. For American bomber crews, jet interceptors would be a deadly threat but not an insurmountable barrier. Nor would jets wholly supplant prop-planes, particularly on the Eastern Front where little strategic bombing occurred, as early jets simply did not have the range and endurance of existing fighters such as the FW-190, Spitfire and P-51. However their use as interceptors that could quickly achieve altitude and engage enemy jet bombers and reconnaissance aircraft would not only be a benefit but a necessity late in the War. Nor were jet bombers, though they benefited greatly from high speed and altitude, capable of the range and bombload of the venerable Lancaster or B-17 or ultra-modern B-29. For Germany, faced with limited aircraft and a gauntlet of Allied fighters, jet bombers would be a viable solution with limited objectives. For the Allies they would be a welcome addition to an already abundant bomber force.

First Generation Jet Combat Aircraft

Germany

That being the case, the “straight wing” He178-A1 would be developed as the first fighter interceptor in early 1941 using the HeS 8 engine with 500 kgf thrust. At 380kg, this engine was only slightly heavier and more powerful than the HeS 3 but boasted a vastly improved fuel economy, increasing the planes combat endurance. By early 1942 the thrust would increase again to 550 kgf for the He178-A2. This would give a conservative top speed of 635-675 km/h at the proposed service altitude and, with increased fuel capacity, a range of some 400km. By October 1942 the more powerful and more fuel efficient HeS 10 turbofan would become available for the He178-B. The 390 kg HeS 10 would give the He178-B 600-700kgf thrust and a top speed of 700-725 km/h. Initially armed with two 15mm cannon in the wing roots, these were replaced with 20mm cannon in 1942.

Italy

In Italy, the Caproni Campini N.1 was an experimental aircraft considered the first jet-powered airplane to take flight, before the existence of the He 178 was made public. As designed by Campini, the aircraft did not have a jet engine in the sense that we know them today, rather a conventional 900 hp Isotta Fraschini L. 121/R.C. 40 piston engine was used to drive a compressor which forced air into a combustion chamber where it was mixed with fuel and ignited to drive the aircraft forward and included a crude afterburner (producing an additional 35-40 km/h). The first flight was on 27 August 1940 with two aircraft and a non-flying ground testbed eventually constructed. With the appearance of the He178-A1 in the summer of 1941, an attempt was made to obtain turbojet engines from Germany, but despite requests from Antonio Alessio and Count Giovanni Battista Caproni, the Germans delivered only a wooden mock-up of the Heinkel HeS 8 for dimensional tests.

The N.1 airframe had already been redesigned, shortening the nose, creating a single cockpit and moving the wings rearward and giving them a 20-degree rear sweep to maintain center of gravity, producing a relatively modern looking jet fighter. Though the engines output remained unchanged at 700 kgf thrust the lighter and sleeker aircraft, now designated CC.2, achieved a top speed nearing 500 km/h and a 500km range. Armament was 2x 12.7mm HMG’s in the wing roots and 2x 7.7mm MMG’s in the wings. In late 1942, Italy finally began receiving HeS 10 jet engines from Germany which, as a development of the HeS 8, were being produced in large numbers. Although these also produced up to 700kgf thrust, their use eliminated the weight of the V-12 engine to boost both speed and range. In mid 1943 the improved CC.3, powered by the HeS 10 and with additional fuel capacity achieved a top speed of some 650km/h with a range of about 700km. Armament was now 2x 20mm cannon in the wing roots and 2x 12.7mm HMG’s in the wings. As the CC.3 were built in Caproni’s Milan factories, these aircraft continued to be used by the National Republican Air Force, ostensibly part of the forces of the Benito Mussolini’s Fascist state in northern Italy, the Italian Social Republic, after 8 Sept 1943.

Britain

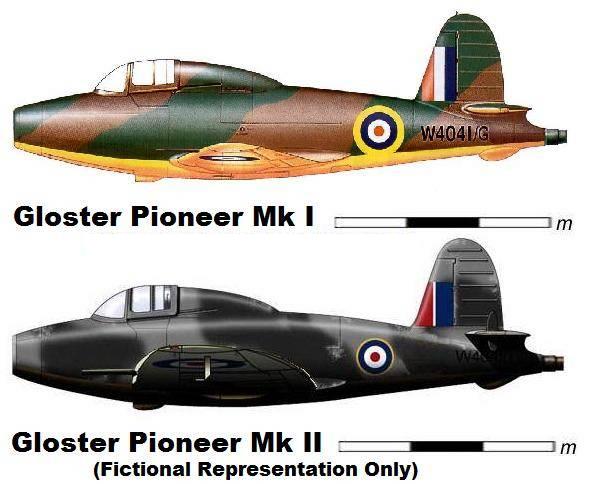

Appearance of the He178 and CC.2 in the bomber interception role in the summer and late fall of 1941 would undoubtedly serve to remind the British Air Ministry of the importance of developing their own operational jet fighter in the form of the Gloster E.28/39 armed with 4x 7.7 mm MMG’s. Powered by the 318kg W.1 turbojet engine producing 390 kgf thrust the 1941 Gloster Pioneer MkI initially achieved a top speed of 544km/h and a range of 656km. This was improved by the use of increasingly refined versions of the engine over the following months. By March 1943 the Pioneer MkII would sport the “universal wing” as used on the Spitfire MkV and the W.1A engine producing 660kgf thrust. This would increase its top speed to 730 km/h while range was maintained by the additional fuel capacity. Standard armament would be 2x 20mm cannon and 4x 7.7mm MMG’s mounted in the wings.

In 1942, due to problems with the Whittle W2 jet engine that were expected to delay production of the Gloster Meteor, the Air Ministry issued Specification E.5/42 asking for a design which would use only one engine rather than the two. In response Gloster produced a design based on the Pioneer for a low-winged monoplane with a highly tapered wing and a T-tail, to be powered by a single Halford H.1 or Metropolitan-Vickers F.2 engine fed by intakes in the wing roots.

As the H.1 was destined for the Vampire and the Welland for the Meteor, the 1088kgf thrust F.2/2 engine was chosen by default and, because of similarities with the E.5/42 concept, Gloster expected that full production of the GA.1 would be swift and relatively easy. Construction of two GA.1 prototypes began in 1943 and these both flew in November, experiencing few problems except for engine overheating. This was solved by installing F.2/3 engines, raising the thrust to 1224kgf in the process, and Gloster subcontracted Supermarine to begin production in April 1944 while they began producing the Meteor. Armed with 4x 20mm cannon, the Gloster Swift Mk I had a top speed was 798 km/h with a range of 660 kms. The Mk II, powered by the 1474kgf F.2/4, first appeared in mid-1945 and was capable of 820kh/h.

USA

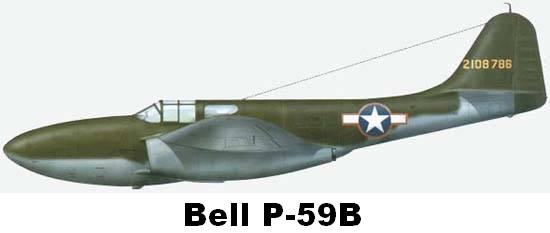

Major General Henry H. Arnold became aware of the United Kingdom’s jet program when he attended a demonstration of the Gloster E.28/39 in April 1941. On 9 January 1942 the design of the first American jet fighter aircraft was finalized and construction of the Bell XP-59 began, using an American version of the Power Jets W.1. On 12 September 1942, the first XP-59A was sent to Muroc Army Air Field (today, Edwards Air Force Base) in California for testing and made its first flight in October. Thirteen service test YP-59As were delivered in June 1943 but compared very unfavorably with British and German jets that were already flying.

With casualties inflicted by enemy jet fighters over Germany steadily mounting, a combat capable jet fighter became a national imperative and, while work continued on the Aerocobra’s airframe to reduce drag, the search began for a much more powerful engine. Designers settled on the Allis-Chalmers J36, an American version of the de Havilland Goblin I initially selected to become the primary engine of the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star. With this engine producing 1043 kgf thrust in the redesigned P-59A, used as a jet trainer, and 1225 kgf thrust in the front line P-59B the USAAF began receiving production Aerocobras in August 1944. In 1945, when replaced in the fighter role by the P80, the 1406kgf thrust Goblin II powered P-59C was seconded to the fighter-bomber role, a task for which it proved itself more than capable.

USSR

Soviet research and development of rocket-powered aircraft began with Sergey Korolev’s GIRD-6 project in 1932. After a long series of unmanned tests of vehicles, Sergey Korolev’s RP-318-1 rocket plane flew on Feb 28, 1940 and on July 12, the Council of People’s Commissioners (SNK) called for the development of high-speed stratospheric aircraft. On June 22, Operation Barbarossa brought the Soviet Union into World War II and the rocket-powered interceptor suddenly became important. After giving a report at the Kremlin, Project-G engineers were ordered to build the plane and were given only 35 days to do so. The official order was dated August 1, but work began in late July with the engineers literally living at the factory until the planes were finished. At the same time as the Blizhnii Istrebitel (close-range fighter), the Kostikov-302 experimental plane was designed and was powered by a liquid fuel rocket for take-off and ramjet engines for flight. By 1940 the idea of the ramjet was familiar in the Soviet Union, mainly to boost the speed of piston-engined fighters, but Mikhail Tikhonravov had the better idea of making a simpler and lighter fighter with a liquid-propellant rocket in the tail and ramjets under the wings. In October, most of Moscow’s war industry evacuated to the Urals with the Bereznyak-Isaev team stationed in Bilimbay, and the Kostikov team in Sverdlovsk, about 60 km away.

On May 15 the first flight of BI-1 was made, reaching an altitude of 840 meters and a maximum speed of 400 km/h. The second flight on Jan 10, 1943, reached 1100 meters but with the engine still throttled back for a maximum speed of 400 km/h. The third flight was made on Jan 12 (some sources say Feb 10) with the engine opened up to full thrust of 1100kgf and a speed of 675 km/h and a maximum altitude of 2190 meters were achieved. Later flights reached a maximum altitude of 4000 meters with a maximum rate of climb of 83 meters per second with a full load of ammunition. On March 27, during a low-altitude test flight, Backchivandzhi pushed the aircraft’s speed to an estimated velocity of 990 km/h, but lost control due to the effects of transonic velocity and crashed. While development of the rocket plane continued, the BI-4 model was combined with the Kostikov 302 design, which was fitted with a pair of DM-4 ramjet engines for sustained flight, and was flown for the first time in August 1943. Designated as the BI-6, it was used as the template for the mass production of 30 aircraft in late 1943 and 50 aircraft in 1944. It was powered by a Dushkin-Isaev D1A-1100 Rocket Engine producing 1100kgf thrust for one minute (with 350 kg of propellant) and 2x Merkulov DM-4 Ramjets to maintain a speed over 800km/h for 30 minutes. Their only mission was to intercept high-speed, high-altitude Germany jet bombers and reconnaissance aircraft. Two 20mm ShVAK cannon were mounted in the nose and two more in the bottom of the forward fuselage, each with 100 rounds.

Second Generation Jet Combat Aircraft

Germany

Building on lessons learned from the He 178, the Heinkel Company began the He 280 project on its own initiative in late 1939. Ernst Heinkel designed a smaller jet fighter airframe for the He 280 that was well matched to the lower-thrust jet engines available in 1941. It had a typical Heinkel fighter fuselage, elliptically-shaped wings and a dihedralled tailplane with twin fins and rudders. The landing gear was of the retractable tricycle type with very little ground clearance. Originally powered by HeS 8 engines, the first prototype was completed in the summer of 1940 and first flight was on 30 March 1941. The type was then demonstrated to Ernst Udet, head of RLM’s development wing, on 5 April, reaching a top speed of 820km/h. One benefit of the He 280 which impressed the political leadership was the fact that the jet engines could burn kerosene, which requires much less expense and refining than the high-octane fuel used by piston-engine aircraft. The He 280 could have gone into production by late 1941 but development delays with the proposed HeS 30 engines meant that it didn’t enter production until late 1942. The HeS 30, initially produced 910kgf thrust and would eventually reach 1125kgf thrust, bringing the new fighters top speed to 900 km/h and 965 km/h with a range of 1050 km. Both the A1 and A2 variants of this aircraft were armed with 3 × 20 mm cannons in the nose

Plans for Messerschmitt Me 262 were first drawn up in April 1939 but progression of the original design into service was delayed greatly by technical issues involving the new jet engines. Though very similar to the plane that eventually entered service, the straight wings received 18.5 degrees of sweep when the proposed engines proved to be heavier than originally expected, primarily to position the center of lift properly relative to the centre of mass. The first test flights began on 18 April 1941 and airframe modifications were complete by 1942 but, hampered by the lack of engines, serial production did not begin until mid1943 when fully reliable examples of the 900kgf Jumo 004B became available. Test aircraft were delivered in April 1943, but Hitler insisted that they be developed into a ground attack aircraft, stressing the possibility of using them as an attack aircraft for anti-shipping to counter an expected invasion of Europe. In tests, German pilots complained that bombs had little chance of hitting their targets and it was suggested that a forward-firing recoilless weapon would be much more effective. To that end 150 mm artillery rocket launcher tubes, developed for the Nebelwerfer in 1941, were mounted to the bomb hardpoints with great success. Me 262-A1 fighters began to arrive in numbers in June but production Me 262-A2 fighter/bombers and Me 262-B/U night fighters wouldn’t become available until Jan 1944. At this time the Me 262’s switched to the 1050kgf thrust Jumo 004D and 004E engines. Fighters would be armed with 4x 30mm cannon and fighter/bombers with 2x 30mm cannon and 2x rockets. Top speeds were between 900km/h and 1000km/h.

When the U.S. 8th Air Force re-opened its bombing campaign on Germany in early 1944, destroying production centers, airbases, railways and roadways, logistics soon became a serious problem for the Luftwaffe, maintaining aircraft in fighting condition almost impossible, and having enough fuel for a complete mission profile even more difficult. To compensate, the RLM suggested that a new aircraft design be built, one so inexpensive that if a machine was damaged or worn out, it could simply be discarded. Thus was born the concept of the “throwaway fighter”. The requirement, specifying a single-seat fighter, powered by a single jet engine, was issued 10 September 1944, with basic designs to be returned within 10 days and to start large scale production by 1 January 1945. Heinkel had already been working on a series of “paper projects” for light single-engine fighters over the last year as a replacement for the He 178 and had gone so far as to build and test several models and conduct some wind tunnel testing.

Heinkel had designed a small aircraft with a sleek, streamlined fuselage and the turbojet mounted in a pod nacelle uniquely situated atop the fuselage directly aft of the cockpit. Twin vertical tailfins were mounted at the ends of highly dihedralled horizontal tailplanes to clear the jet exhaust, a high-mounted straight wing with a forward-swept trailing edge and shallow dihedral, and tricycle landing gear that retracted into the fuselage. The main structure would use cheap and unsophisticated parts made of wood and other non-strategic materials and, more importantly, could be assembled by semi- and non-skilled labor. The prototype flew within an astoundingly short period of time: the design was chosen on 25 September and first flew on 6 December with fair success at a speed of 840 km/h, less than 90 days later. In January 1945 the first 46 aircraft were delivered for service testing and February saw the first deliveries to operational units. At 2800 kg, the aircraft was among the fastest aircraft in the air with a maximum airspeed of 839 km/h at 6000 meter, but could reach 905 km/h using a short burst extra thrust. The He 162-A finally saw combat in mid-April but the majority of losses were due to flameouts and sporadic structural failures. The He 162’s 30-minute fuel capacity also caused problems but the difficulties experienced by the He 162 were caused mainly by its rush into production, not by any inherent design flaws. The He 162-B, a proposed follow-on to be armed with twin 30 mm cannon planned for 1946, was captured prior to flight tests by Allied troops at war’s end. It included a more powerful Heinkel-Hirth HeS 011A turbojet, a stretched fuselage to provide more fuel and endurance as well as increased wingspan and swept wings with proper dihedral and a new V-tail stabilizing surface assembly.

Britain

George Carter, Gloster’s chief designer, presented initial proposals for a twin-engined jet fighter in August 1940. The Meteor’s construction was all-metal with a tricycle undercarriage and conventional low, straight wings, featuring turbojets mid-mounted in the wings with a high-mounted tailplane to keep it clear of the jet exhaust. Eight prototypes were produced but delays with getting type approval for the engines meant that it was not until the following year (1942) that flights took place with the fifth prototype, powered by two de Havilland Halford H.1 engines owing to problems with the intended Whittle W.2 engines, the first to become airborne on 5 March 1943. On 12 January 1944, the first production Meteor Mk I took to the air. It was essentially identical to the prototypes except for the addition of four nose-mounted 20 mm Hispano Mk V cannons and some changes to the canopy to improve all-round visibility. The engines were switched to the 771kgf Rolls-Royce Welland, giving the aircraft a maximum speed of 670 km/h at 3,000 m and a range of 1,610 km. The first 20 aircraft were delivered to the Royal Air Force on 1 June 1944 in time to participate in the D-Day landings where the Meteors flew armed reconnaissance and ground attack operations without encountering any German jet fighters. On 18 December 1944, 616 Squadron exchanged its Mk Is for the much improved Meteor Mk IIIs. These featured the longer nacelles to counter compressibility buffeting at high speed, the new 907kgf Rolls-Royce Derwent engines that produced speeds of 748km/h, increased fuel capacity for a range of 811kms, and a new larger, more strongly raked bubble canopy. The war ended with the Meteors of 616 Sqn having destroyed 46 German aircraft of all types.

The de Havilland Vampire was considered to be a largely experimental design due to its unorthodox arrangement, unlike the Gloster Meteor which was always specified for production. De Havilland were approached to produce an airframe for the proposed Halford H.1 and their design, a mixed wood and metal construction , twin-boom, tricycle undercarriage aircraft armed with four cannons, had conventional straight mid-wings and a single jet engine placed in an egg-shaped, aluminum-skinned fuselage, exhausting in a straight line. Although design work began two years after the Meteor, the 953kgf thrust Goblin I powered Vampire prototype’s first flight was on 20 September 1943, only six months after the Meteor’s maiden flight. The Vampire Mk I was ordered into production in May 1944 and the first examples began flying in August, with most being built by English Electric Aircraft due to the pressures on de Havilland’s production facilities. Although eagerly taken into service by the RAF, the improved 1225kgf thrust Goblin I initially gave the aircraft a disappointingly limited range, a common problem with all the early jets, and later Mark’s were distinguished by greatly increased fuel capacities. Armed with 4x 20mm cannon, the Mk I had a top speed of 845 km/h and a range of 1175 kms.

USA

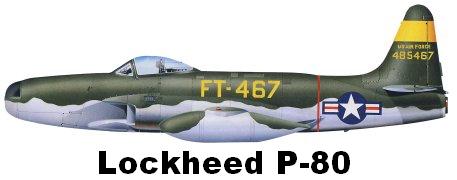

The impetus behind the development of the P-80 was the appearance of the German Messerschmitt Me 262 jet in the spring of 1943. Concept work began with a design being built around the blueprint dimensions of a British de Havilland H-1 B turbojet, a powerplant to which the design team did not have actual access, with the engine integrated within the main fuselage, a design previously used in the pioneering Gloster Pioneer. It was a conventional, all-metal airframe with a slim low wing and tricycle undercarriage (landing gear). The first prototype flew on 8 January 1944 and the Shooting Star began to enter service in late 1944. The initial production order was for 344 P-80As after USAAF acceptance in February 1945 and a total of 83 P-80s had been delivered by the end of July 1945 but because of the delay in acquiring a suitable engine the Shooting Star saw no combat in World War II.

Jet Bomber Aircraft

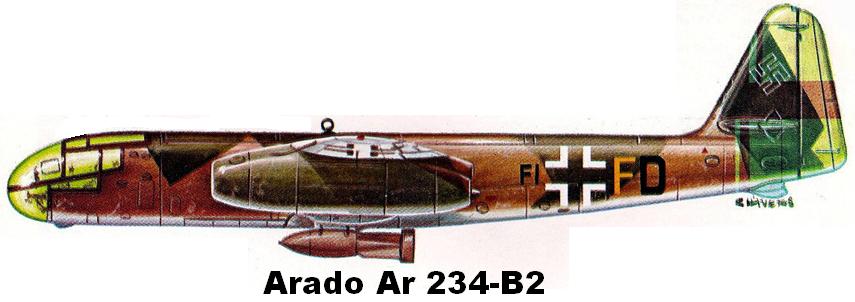

Arado Ar 234

In the autumn of 1940, the RLM offered a tender for a jet-powered high-speed reconnaissance aircraft. Arado was the only company to respond, offering a high-wing conventional-looking design with a Junkers Jumo 004 engine under each wing. Two prototypes of Ar 234 were largely complete before the end of 1941, but the Jumo 004 engines were not ready, and would not be ready until February 1943. The design called for two 750kg engines producing 900kgf thrust but the best available production engine was the 380kg HeS 8, producing 500kgf of thrust. As an interim mesure, it was decided to mount four of these in individual nacelles or in twin nacelles under each wing and the Ar 234 V1 made its first flight on 15 June 1942. The Ar 234 V2 prototype, with a top speed of 780 km/h and range of 1995km, made history on 2 August 1942 as the first jet aircraft ever to fly a reconnaissance mission. The RLM had already seen the promise of the design and in July asked Arado to supply two more prototypes of a “fast bomber” version as the Ar 234B. Since the aircraft was very slender and entirely filled with fuel tanks, there was no room for an internal bomb bay and the bombload had to be carried on external racks, with the added weight and drag of a full bombload reducing the speed. The B models were slightly wider at the mid-fuselage to house the main landing gear, with a fuel tank present in the mid-fuselage location on the eight earlier trolley/skid equipped prototype aircraft having to be deleted for the retracted main gear’s accommodation, and with full bombload the plane could only reach 668 km/h at altitude. This was still better than any bomber the Luftwaffe had at the time, and made it the only bomber with any hope of surviving the massive Allied air forces. The normal bombload consisted of two 500 kg bombs suspended from between the engine nacelles or one large 1,000 kg bomb semi-recessed in the underside of the fuselage with maximum bombload being 1,500 kg.

Production lines were already being set up, and 20 B-0 pre-production aircraft were delivered by the end of June 1943. Meanwhile, the prototypes were sent forward in the reconnaissance role and, in most cases, it appears they were never even detected, cruising at about 740 km/h at over 9,100 m. Overall from the summer of 1943 until February 1944, when production was switched to the C variant, a total of 210 aircraft were built. The Ar 234C was equipped with four 562 kg BMW 003A engines producing 800 kgf, mounted in a pair of twin-engine nacelles. An improved cockpit design, with a slightly bulged outline for the upper contour, also used a much-simplified window design for ease of production. Airspeed was found to be about 20% higher than the B series and the faster climb to altitude meant more efficient flight and increased range.

Ar 234B-0 : 20 pre-production aircraft.

Ar 234B-1 : Reconnaissance version, equipped with two cameras.

Ar 234B-2 : Bomber version, with a maximum bombload of 2,000 kg.

Ar 234C-1 : BMW 003A engined version of the Ar 234B-1.

Ar 234C-2 : BMW 003A engined version of the Ar 234B-2.

Ar 234C-3 : Multi-purpose version, armed with two 20 mm MG 151/20

cannons beneath the nose.

Heinkel He 343

The Heinkel He 343 was a four-engine jet bomber project designed along the lines of an enlarged Arado Ar 234 V3, shortening the development time and for re-use of existing parts, at the beginning of 1943. For a choice of engines, the Junkers Jumo 004 and the Heinkel HeS 011 were planned but the Jumo 004 was earmarked for Me-262 production. The 950 kg turbofan engine, combining elements of the HeS10 and HeS 30, weight much the same as the Jumo 004 but operated at higher thrust levels, 1225kgf as opposed to about 900 kgf. By the end of 1943 work was nearly finished by the Heinkel engineers, with parts for the He 343 prototype aircraft either under fabrication or in a finished state. After much test, first flight was conducted on 24 July 1944 and it was found to be easy to fly with responsive controls. Originally planed in two versions, only the A-1 bomber and A-2 reconnaissance aircraft were brought into service in late 1944. They could carry an internal payload of 3,000 kg, bombs or additional fuel, at a top speed of 910kh/h and range of 2800km and both variants were armed with two 20 mm MG 151/20 cannons beneath the nose.

Gloster Jet Bombers

In August 1942, Gloster’s George Carter produced a design for a 4-jet bomber with a 25.6m wing span and 20m length simply known as the Gloster Jet Bomber. This was the first British design for a bomber using jet power. Carter explained this was an on-going project and subsequently completed drawings for the improved and revised design P.109 in November the same year. The P.109 looked like a very large Meteor, with four Whittle W2B (Derwent) jets housed in common nacelles mid-wing. Each pair of engines shared a common intake and a common exhaust slot. Carter thought this design was probably the best that could be arrived at using the W2Bs. It had an estimated speed of 730km/h at 10,973m with a bombload of 1815kg, running on 4x Derwent engines of 907kgf thrust. The P.108 was the larger aircraft with a 3630kg bombload, but achieved a similar performance when powered by 4x 1225kgf Metrovic F2/3 engines. In 1943, the Government took over the ownership and management of Shorts under Defense Regulation 78, assigning the construction of the P.108 “Cumbria” to the Shorts factory established at White Cross Bay, Lake Windermere, and the P.109 “Comet” to Short subcontractor Austin Motors at Longbridge, Birmingham.

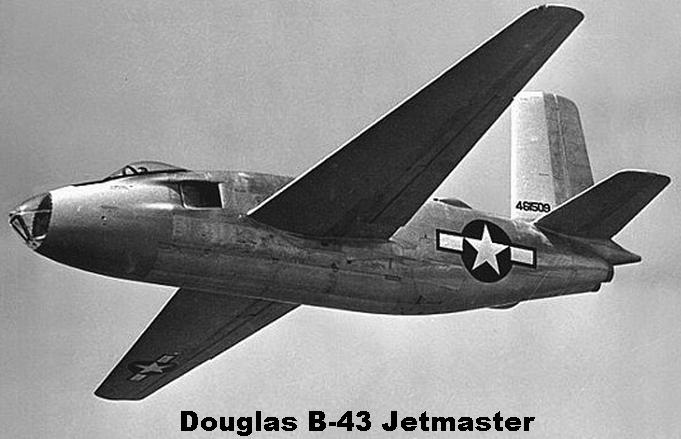

Douglas XB-43 Jetmaster

United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) leaders in the Air Materiel Command began to consider the possibilities of jet-propelled bombers as far back as October 1943 when the War Department, alarmed by German jet bombers like the Arado Ar 234, called for a new family of jet bombers. At that time, Douglas Aircraft was just beginning to design a promising twin-engine bomber designated the XB-42 as a private venture. The Douglas design team convinced the Army that modifying the XB-42 airframe into the first XB-43 was a relatively straightforward process that would save time and money compared to developing a brand new design. Two General Electric (GE) J35 turbojets were installed in the rear fuselage fed by air intakes in each side of the fuselage, leaving the laminar-airfoil wing clean of any drag-inducing pylon mounts or engine cowlings. The company was poised to roll out as many as 200 B-43s per month in two versions: a bomber equipped with a clear plastic nose for the bombardier, and an attack aircraft without the clear nose and bombing station but carrying up to 16 forward-firing 12.7mm machine guns and 36x 127mm rockets. Douglas Aircraft was keen to mass produce the new bomber but the USAAF only ordered 50 of the bomber type. The USAAF was already moving ahead with a new bomber, the North American XB-45 Tornado, designed from the outset for turbojet power and promising a quantum leap in every category of performance.

[End of Article]