The American Civil War was primarily a war of manoeuvre and remained so even when trench warfare was employed. During the war, fortifications were used in siege and counter-siege and as jumping off points for various attacks by both sides. The concept of Armoured Tractor Artillery would be unlikely to occur to anyone until the horrors and high casualties of trench warfare were actually experienced, the first instance of which would have been the Battle of Fredericksburg (December 11–15, 1862). Here, Union casualties were more than three times as heavy as those suffered by the Confederates and a visitor to the battlefield described the battle to U.S. President Abraham Lincoln as “butchery.” President Lincoln took a personal interest in the conduct of the war and would often visit front lines and HQ’s (to the consternation of those around him) and was always interested in innovative technology, such as early machineguns and breech-loading and repeating rifles, that would help the Union side. Such interest was not shared by the high command of the Army who felt that existing rifled muskets and RML artillery was more than adequate for the job at hand. To them the low production rates, intricacy and expense of such weapons (and their appetite for ammunition) cut into the availability and supply of the real, and proven, weapons of war.

The Engine

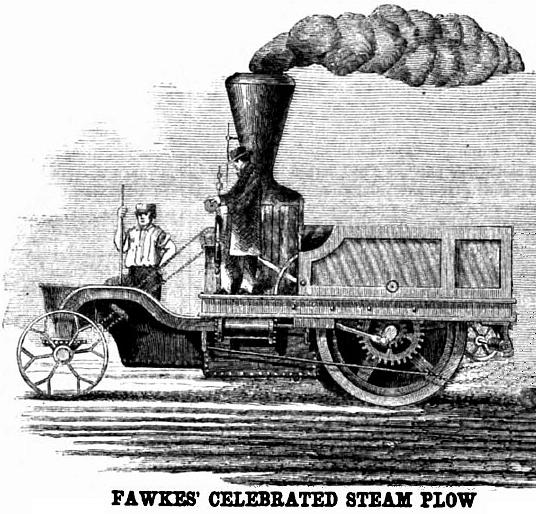

Joseph Fawkes’ steam plough of 1858 would be an excellent basis for the Armoured Artillery Tractor. He demonstrated his engine at the state fair in Centralia, Illinois on September 17, 1858 by ploughing a strip of land baked by summer drought. However, when Fawkes attempted another ploughing exhibition at Decatur, Illinois some two months later, the ground was soft due to heavy rains and the 10-ton machine bogged down. In 1861 Fawkes again exhibited his invention at the ‘United States Fair’ in Chicago in competition with other steam ploughs designed by James Waters of Detroit (which broke down early on) and John Van Doren of Chicago. The engine of Fawkes’ machine derived its traction from a big driving drum rather than from wheels while the competing machine got its traction from two driving wheels some 12 feet in diameter, similar to the British Fowler steam tractor. His drum cylinder machine traveled on the surface of the soil with no difficulty while the big drivers on the other entry sank into the ground. Fawkes’ plough proved superior in this test, in which the engine was run up the various grades of the fair grounds, passing into a gully and moving out without the least difficulty. Steam, by the indicator, was marked at only 62% and upon measurement the grade was found to be one foot vertical to four set on the horizontal line (about 7%). The engine could also be safely run across an inclined plane of thirty degrees, because of its great breadth of base (six feet) and low centre of gravity. Fawkes, seeing a business opportunity, moved to Illinois with the idea of manufacturing steam ploughs but the Civil War intervened.

The main frame was of iron, 8 feet wide by 12 feet long, resting on the axle of a roller (driver), 6 feet in diameter and 6 feet wide. One cylinder, 9” in diameter with 15” stroke was provided on each side of the boiler , which may be got up to steam in fifteen minutes, although twice that time is usually necessary. The drum is placed about midway between the front and back of the machine; before it depends the fire-box, and over and behind it is the tank; so that, when the boiler and tank are full, they nearly counterbalance each other on the axles of the driving drum. The fuel consumed in one hour during the Chicago test was one hundred and seventy pounds of inferior coal and wood evaporating about one hundred and fifty gallons of water however it was determined that, with fuel of even ordinary quality, it could carry water sufficient for a three hours run. The machine could run without injury through water twelve inches deep and, with its drum and guiding wheels, present a surface of one hundred and two inches, making it less liable to miring in sloughs. Barring this, the machine would continue to have problems traversing soft, sandy or rocky ground, though mechanical reliability was considered good for the time. At full power the engine developed up to 30 (indicated) horsepower and cost upwards of $2500 ($68,698 in 2016).

One major improvement to this machine would be the use of a liquid fuel, Kerosene, while still allowing for the use of solid fuel as a contingency. By 1860 kerosene, commonly called “coal oil”, was being produced in quantity from multiple sources such as torbanite, bituminous coal, oil shale and crude oil. Fed by wells in Pennsylvania, the illuminating and heating oil industry in the United States completely switched over to less expensive petroleum in the 1860s and kerosene lamps, heaters and stoves became more common. To decrease the possibility of catastrophic failure, particularly as kerosene was often cut with other distillates such as naphtha at that time, I would place the fuel tank inside a water jacket over the roller and between the water tank and boiler. In fact, the fuel and water tanks could conceivably be combined into a single unit – just don’t get the two confused. I would also switch the guide wheels over to a single roller (as per early steam rollers) to further disperse weight and add slats to the main drum, as was often done on tractor wheels, to improve traction. If it is found necessary, outrider wheels could be added to the drum and guide rollers (on an extended axel) and the armoured skirt adjusted accordingly.

Armament

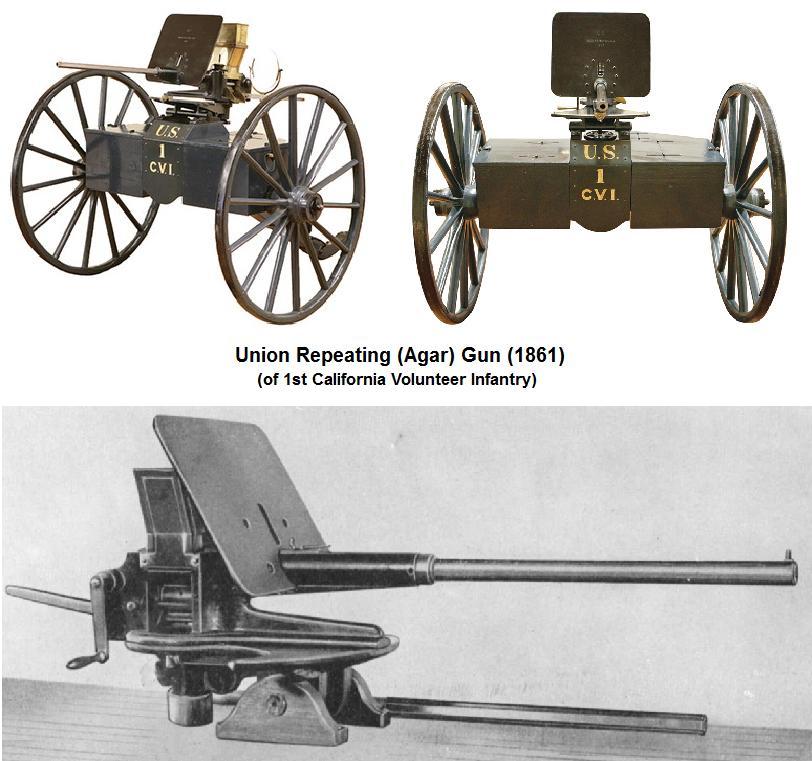

There were two machinegun like weapons available to arm the Armoured Tractor. These were the Agar Gun, of which the Union Army eventually purchased a total of 64 (in 1861/62), and the Gatling Gun, of which 12 were purchased personally by Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, commanding the Army of the James, and employed during the siege of Petersburg, Virginia (June 1864). The Gatling Gun was not adopted by the Army until 1866 but the United States Navy purchased eight Gatling guns to be fitted on gunboats. As early multi-barrel guns were approximately the size and weight of contemporary artillery pieces my preference is toward the lighter Agar Gun, which was at least part of the Union inventory even if it was greatly under appreciated. The Agar Gun fired standard .58 calibre/65 grain paper cartridges loaded into re-usable metal tubes with a separate percussion cap fitted to a nipple at the rear, effectively creating a centerfire cartridge. These were then placed into a funnel shaped hopper, which gave the weapon its “coffee mill” appearance, and fed into the weapon and fired using a hand crank located at the rear of the gun. The special steel tubes used to hold the cartridges were heavy and expensive but were a required component of the system as, locked in place by a wedge shaped block, they comprised the firing chamber of the weapon. The single barrel design proved prone to overheating and the weapon was also prone to jamming so that the rate of fire was mechanically limited to 120 rounds per minute, which helped to control this. During a 1000 round firing test in 1861 (at 100 rds/m) the barrel reportedly became incandescent and the lining melted, which may well be the first recorded instance of a gunner “burning out” a barrel. For that reason the gun was designed to allow barrels to be quickly replaced and spares were always carried. Although a cooling system was devised (involving a fan powered by the crank), overheating in normal use could be prevented entirely by extending the existing shroud over the barrel (as per the 1911 Lewis gun) or adding a water-jacket (as per Confederate 1861 Hughes 1.5-in/38mm gun and 1884 Maxim Gun) to the design. The Agar Gun had an effective range of about 800 yards, which was roughly the same as the range of the rifle-muskets used by infantry, and each gun cost a minimum of $735 ($20,197 in 2016).

The Whitworth rifled breech-loading gun, designed by Joseph Whitworth and manufactured in England, was a rare gun during the American Civil War with only 7 guns being used by the Union (and 5 by the Confederacy) at a cost of $1183 each ($32,507 in 2016). It should be noted that the Union also had 5 Whitworth RML guns while the Confederacy may have had as many as 33. The Whitworth RBL guns would be available for use after the Peninsula Campaign in 1862 but the unique ammunition (solid, bursting and case) is expensive and the breech-loading mechanism was prone to jamming. Patented in 1855, it had a 2.75 inch (70 mm) bore and a tube length of 104 inches and could fire a 12-pound 11-ounce projectile over a range of about 6 miles. Though used by both the Confederacy and the Union, it was rejected by the British Army who preferred the guns from Armstrong. Armstrong’s system was adopted by the British in 1858 and initially he only produced smaller artillery pieces: 6-pounder (2.5-in/64 mm) mountain or light field guns, 9-pounder (3-in/76 mm) field guns for horse artillery, and 12-pounder (3-in/76 mm) field guns. If the Whitworth gun is to be used I would recommend reducing the barrel length to 66 inches (as per Model 1857 12-pdr gun/howitzer) to reduce the recoil that must be absorbed entirely by the gun mount and vehicle structure. If Armstrong guns are to be purchased instead, the less expensive (at $727) 6-pdr light field gun would be quite usable as would the 9-pdr.

Armour

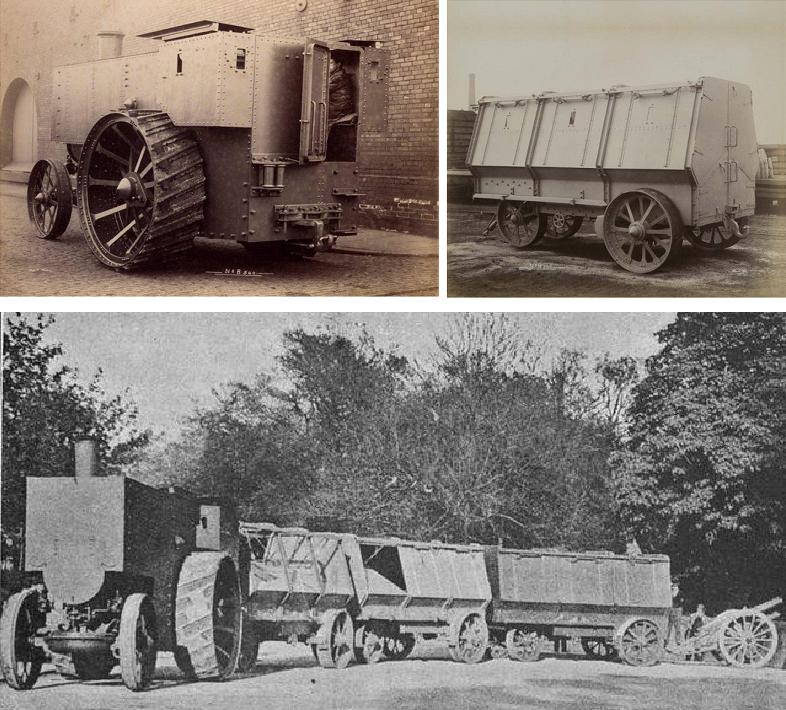

If the Union were to build an armoured tractor during the Civil War, it would probably look very much like the armoured Fowler B.5 (115 ihp) steam tractors that the British War Office deployed to South Africa, along with armoured trucks, during the 2nd Anglo-Boer War (1899 – 1902). The armour on these vehicle provided protection from rifle fire and exploding shells (but not a direct hit) and completely enclosed the body of the machine in a slab-sided structure, with only the chimney projecting. Access to the vehicle was achieved by means of a door through the armour at the rear and three loopholes were provided on each side for the use of the (two man) crew’s weapons. It weighed some 15 tons complete with armour and could run as fast as 10 miles per hour on an improved level road and about half that across level fields. The armoured trucks which went with the tractor were four wheelers with the front axle, which incorporated the tow-bar, being mounted on a turntable. The armour on each side was in three sections, which could be hinged inwards independently, and each section carried a loophole but there was no overhead armour protection. These trucks could mount 10 riflemen or a light artillery piece and gun crew.

At only 30 ihp, our Fawkes Armoured Tractor would in no way be able to meet the capabilities of the later Fowler. Under load, the vehicle could travel at a “quick” 2 mph, roughly half the speed of a WWI Mk.I tank, cross country. It should be possible to maintain this speed if armour is restricted to 2.5 tons at 0.20 inches overall, sufficient to protect against a black powder propelled musket or rifle ball (the Confederate Enfield had a muzzle velocity of about 900 fps) and shrapnel from exploding shells. However, as with the Fowler, a direct hit by solid shot would certainly destroy the machine and highly accurate Confederate long-range Whitworth Guns and frontline rapid-firing 1.57-inch/40 mm rifled Williams Guns (of which the CSA had 42 in 7 batteries) would be a particular nuisance. There were also 50-or-so quick-firing 1.50-inch/38mm smoothbore and 2-inch/51mm rifled Hughes Guns that had been deployed in the Western/Trans-Mississippi theatre of operations, some of which may have found their way east during the final years of the war.

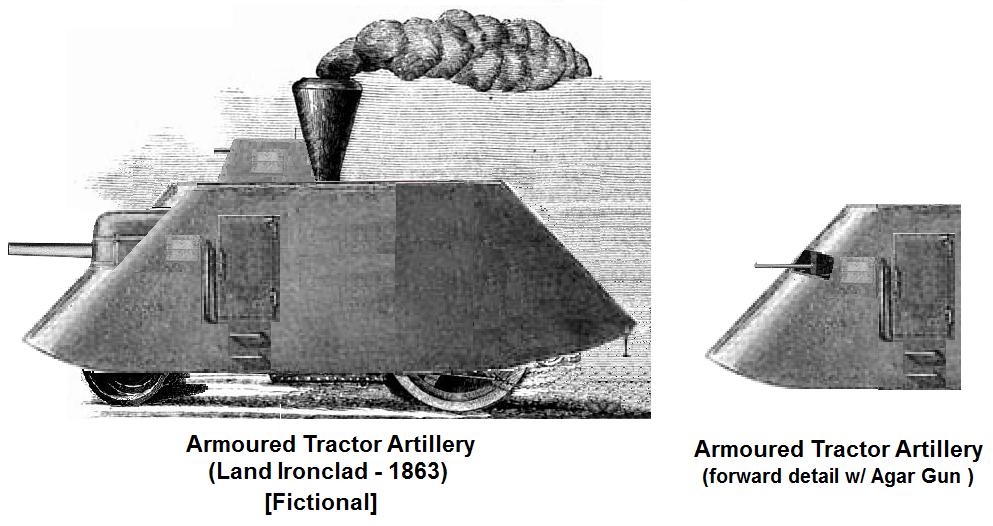

Rather than a slab-sided armoured body I have chosen to use something more like that of the 1902 Simms Motor War Car to provide a sloping surface. The Agar guns would be fired through ports on either side of the bow for the females and the rifled breach loader via a single barbette at the bow for the male (as per German A7V of WWI). The interior would be laid out in two levels accessed via a small ladder next to the armoured hatchway. The upper control level where the driver/mechanic and commander would be seated (so as to allow more space below) and the lower gun level for the guns, gun crew and ammunition. Sufficient ammunition for 20 minutes of combat would be carried, at a rate of fire of 100 rds/min for the Agar Guns and 6 rds/min for the Whitworth Gun (plus 6 rds of case shot). Each level would be open to the other so that the commander is able to provide direction to the gun crew below. At the centreline, between the boiler and crew compartment, there will be a firewall to control the transfer of heat to the crew compartment and to protect the crew should the boiler or fuel explode. Louvered vents along the top edge of the crew compartment and mechanical compartment (above the door line) would also aid in cooling. Louvered armoured plates above the mechanical compartment would be hinged and dogged so as to blow outward in case of explosion and to facilitate refuelling and repair. If necessary, the mechanical compartment can be entered from the crew compartment by uncoupling the internal ladder and opening a small fitted panel in the firewall. Finally, at the rear of the vehicle would be a small storage compartment for vehicle, crew and personal gear accessed via a hinged and latched hatch.

Crew: Male – 4 (driver/mechanic, commander/co-driver, gunner, loader)

Female – 6 (driver/mechanic, commander/co-driver, 2x gunner, 2x loader)

Usage

If a suitable prototype was produced and Lincoln sufficiently impressed, and with a great deal of effort, the first tanks (“females” armed with two Agar Guns) may have been available at Chancellorsville in May 1863 and a full battery at the defence of Harrisburg on 28/29 June 1863. Certainly, by the time of the Overland Campaign in the spring of 1864 General Grant would have had at his disposal the full complement of 9 (“male”) Whitworth Gun tanks, armed with all 7 Union guns and two Confederate guns captured at Gettysburg, and 6 (“female”) Agar Gun tanks, armed with guns ordered purchased by Lincoln and those purchased by General Butler – essentially two mixed batteries and a half-battery of “males”. These would undoubtedly be controlled by the Artillery and, as far as any tactical doctrine went, would be employed against fortified positions and siege lines in direct, close support of attacking infantry. In the defence they would become instant fortifications, being too slow and cumbersome to retreat quickly, creating strong-points that could be utilized by accompanying infantry to establish new defensive lines. Movement over long distances would be facilitated by the Unions extensive rail network, with the tanks loaded onto flatcars for transport. Though they might officially be referred to as Armoured Tractor Artillery or Land Ironclads and unofficially as something like Armadillos or Tortoises or Turtles, I will use the more recognized term “Tank”. If they prove themselves in combat, further tanks could be built by using some of the 33 Agar Guns already in use by the Army of the Potomac (17 of the original 50 were captured by the Confederates at Harpers Ferry in Sept 1862) and the two guns purchased by General Fremont in California. Additional “male” tanks could be built only by purchasing more Whitworth (or Armstrong) Guns, though this would be a hard sell unless they really distinguished themselves, or converting the 5 Union and any captured Confederate Whitworth rifled muzzle loaders into breach loaders (as was done with Ordinance 3-in RML guns post-war). By the time of the siege of Richmond, Grant could well have a brigade of 5 or 6 mixed batteries (in two regiments) at his disposal, what we could call a tank battalion (US) or armoured regiment (BCN) today. Such a brigade could also be supported by dedicated infantry regiments armed with Sharp’s breachloading rifles such as the 1st Pennsylvania Rifles and the 1st Michigan Volunteer Sharpshooters (designated “Rifles”), each with ten rifle companies, a HQ company and supply train. Each section (two vehicles) of a battery would then have a company of infantry assigned to it. At the very least, during the Overland Campaign and Richmond–Petersburg Campaign, he would have available a regiment (of three mixed batteries) of Armoured Tractors supported by a regiment of rifle infantry.

Note: This work is an expansion upon an article written by Jason Torchinsky, dated 15 July 2016, for the site Foxtrot Alpha. That article may be viewed at http://foxtrotalpha.jalopnik.com/why-were-there-no-tanks-in-the-civil-war-1783715159