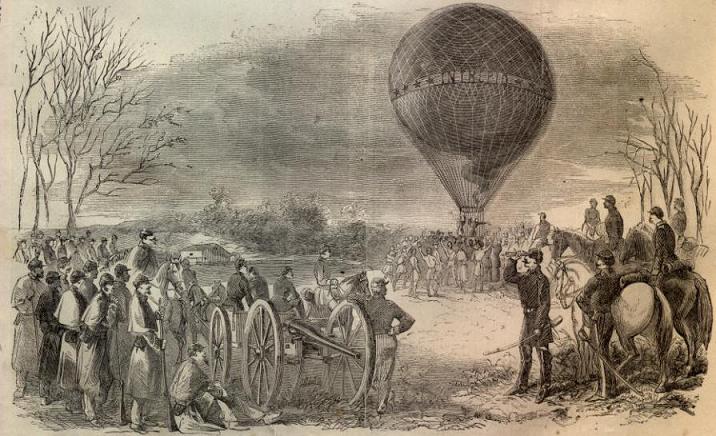

The Union Army Balloon Corps was a branch of the Union Army during the American Civil War, organized as a civilian operation that employed a group of prominent American aeronauts and seven specially built, gas-filled balloons to perform aerial reconnaissance on the Confederate States Army. Thaddeus S. C. Lowe was working on an attempt to make a transatlantic crossing by balloon when the Civil War broke out one week before one of his most important test flights. Subsequently, he offered his aviation expertise to the development of an air-war mechanism through the use of aerostats for reconnaissance purposes, meeting with U.S. President Abraham Lincoln on June 11, 1861 and demonstrating with his own balloon, the Enterprise, in Washington, D.C.. Eventually he was chosen over other candidates to be chief aeronaut of the newly formed Union Army Balloon Corps.

The Balloon Corps, with a hand-selected team of expert aeronauts, served the Union Army from October 1861 until the summer of 1863 at Yorktown, Seven Pines, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and other major battles of the Potomac River and the Virginia Peninsula, sometimes launching from a specially modified Naval “balloon tender”. Initially, Lowe was offered $30 per day for each day his balloon was in use but offered to accept $10 gold per day (colonel’s pay) if he were to be allowed to build more suitable balloons and hire as many men as he needed for $3 currency per day. However, none of the corps ever received a military commission, which often put them at odds with military officers and also left them facing the possibility of being captured and summarily executed as spies.

For all its success, the Balloon Corps was never fully appreciated by the military community, which had little respect for their break-neck operation and regarded them as little more than carnival showmen. Only the generals, whose jobs and reputations were on the line, found them to be of any value while lower-ranking administrators looked with disdain on this band of civilians who, as they perceived them, had no place in the military. The Balloon Corps was eventually assigned to the Army Corps of Engineers and put under the administrative purview of one Captain Cyrus B. Comstock, who did not appreciate a civilian (Lowe) being paid more than he and reduced Lowe’s pay from $10 gold to $3 gold per day. Lowe posted a letter of outrage and resigned his position on 8 April 1863 so that by 1 August 1863 the Corps was no longer used.

The Airship

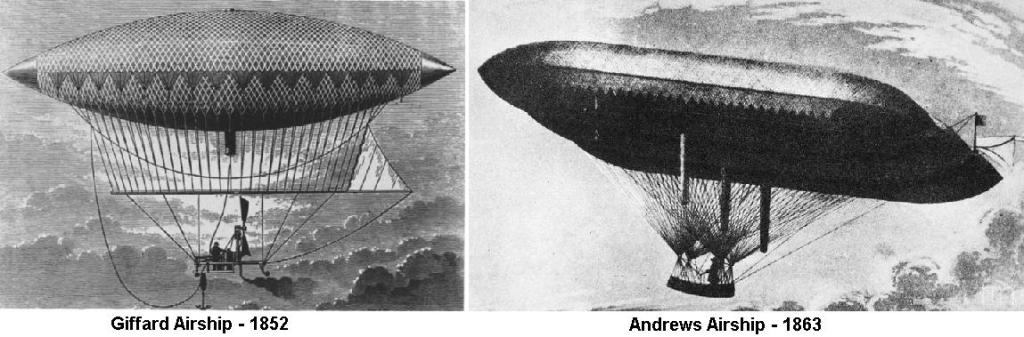

The 19th century saw continual attempts to add methods of propulsion to balloons. In 1851 Australian Dr. William Bland designed an elongated balloon with an estimated lift of 5 tons and a 3.5 ton steam engine (including fuel) driving twin propellers suspended underneath, giving a payload of 1.5 tons and projected top speed of 50 mph. In 1852 Frenchman Henri Giffard became the first person to make an engine-powered flight when he flew 17 mi in a similar steam-powered, hydrogen-filled airship weighing over 400 lb and equipped with a 3 hp steam engine that drove a propeller. In 1863 an American, Dr Solomon Andrews, flew his aereon design – an unpowered, controllable dirigible that had three 80-foot cigar-shaped hydrogen-filled balloons with a rudder and gondola – in New Jersey and offered the device to the US Military during the Civil War but was informed that the Government had little interest in his invention. Manned air-war mechanisms would became important again to the Army when the airship came into existence with motorized propulsion and mechanical means of steering.

Should such a craft be accepted for service by the Union – the Confederacy would be incapable of even beginning such a project – it would be unlikely to be taken on by the Army, which had only just successfully divested itself of the Balloon Corps. Those that had been part of that group would still be available, and smarting at their treatment by the Army, and would be ready allies to Dr Andrews and Mr Marriott (see below) should they have wished to pursue the issue. It would be left to the Navy, with it’s balloon tender experience, to step forward and take the fledgling service under it’s wing, perhaps even enticing Lowe with the rank and pay of Rear-Admiral (matching an offer made by the Brazilian Army in 1864).

I envision the machine itself as being a hydrogen-filled semi-rigid dirigible derived from Dr Andrews’ design, with it’s three distinct 80 ft long (33,000 cu ft) envelopes, mated to a (kerosene fuelled) steam engine as envisioned by Dr Bland and tested by Giffard. A 30 hp steam engine of the time, not unlike that used in the Fawkes steam tractor, would weight something close to the indicated 3.5 tons, including water and fuel. Like the earlier balloons, the envelopes would be of varnished silk with the engine, water, fuel, control surfaces, gondola and any payload affixed to an open detached keel – constructed of lengths of pine connected with steel sockets and braced with piano wire – suspended below. At full power the craft should be able to maintain an average ground speed of at least 35 mph for three hours, easily maintaining direct observation of enemy movements or defences. As these craft would be untethered and free to manoeuvre, communications with ground personnel could be maintained via flag semaphore or optical Morse (heliograph) signalling.

The Aeroplane

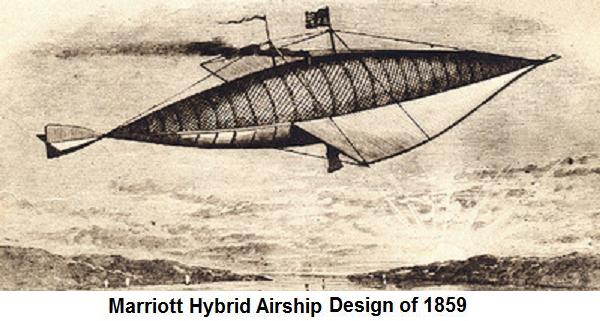

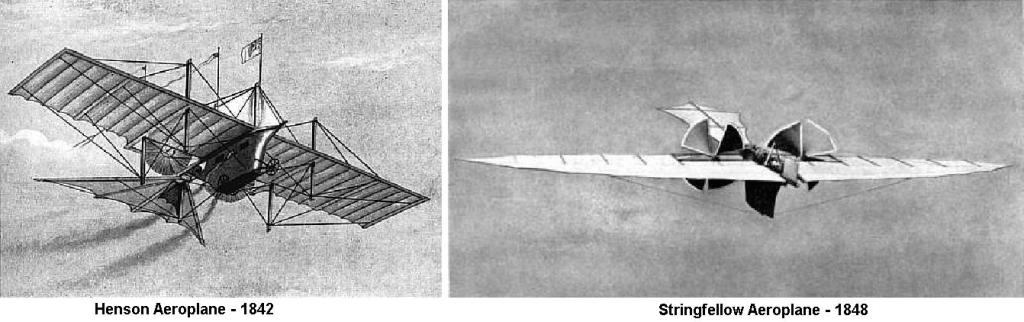

In April 1841 William Samuel Henson patented an improved lightweight steam engine and, with fellow lacemaking-engineer John Stringfellow, designed a large passenger-carrying steam-powered monoplane in 1842. Drawing directly from the work of Sir George Cayley, the “father of the aeroplane”, Henson’s 1842 design for a 150 foot span high-winged monoplane, with a a specially-designed lightweight 50 hp steam engine driving two pusher configuration propellers, broke new ground and he and Stringfellow received a patent on it in 1843. Henson, Stringfellow, Frederick Marriott, and D.E. Colombine, incorporated as the Aerial Transit Company in 1843 in England, with the intention of raising money to construct the flying machine, and attempts were made to fly a small scale model of his design, and a larger model with a 20-foot wing span, between 1844 and 1847, without success. Henson then grew discouraged, married and emigrated in 1849 to the United States, while Stringfellow continued to experiment with aviation.

In 1850, Marriott also left England for the wilds of California where established the San Francisco News Letter and California Advertiser in 1856. He also continued with his interest in aerial enterprises and designed, and eventually built, a hybrid slightly-heavier-than-air airship 37 feet long and 14 feet in overall width, which weighed 84 pounds when not inflated and between 4 and 10 pounds when inflated. It was powered by a steam engine, having one 2″ diameter cylinder with a 3″ stroke, which was capable of generating 8 pounds of steam driving two two-bladed 4 ft. diameter propellers, each mounted within one of two flat wings.

In 1848 Stringfellow achieved the first powered flight using an unmanned 10 ft wingspan steam-powered monoplane employing two contra-rotating propellers. On the first attempt, made indoors, the machine flew ten feet before becoming destabilized, damaging the craft. The second attempt was more successful with the machine achieving some thirty yards of straight and level powered flight. I would base an early piloted aeroplane on this design, sufficiently scaled up to carry one person (about 300%) and powered by two 80 lb, 5 hp, kerosene fired steam engines, each driving a Ericsson screw-type propeller to provide a sustained ground speed of between 10-20 mph depending on conditions. Like many early aircraft, especially monoplanes, this aeroplane would use warping of the wing and rear half of the stabilizer (rather than ailerons and elevator) for lateral (roll) and vertical (pitch) control, with only the vertical, twinned triangular rudder surfaces (controlling yaw) hinged.

Five gallons of water and 2.5 gal of kerosene would provide a flight time of about one hour but these early aeroplanes would remain frail and of little practical use except as aerial scouts during good weather. The basic structural and materials technology of the airframes would mostly consist of hardwood materials with steel connectors, braced with piano wire and covered in linen fabric doped with a flammable stiffener and sealant such as the varnish used in balloons. The heavy steam engines and limited engine power available, as compared to later internal combustion engines, meant that the effective payload would be extremely limited and the need to save weight would mean that the aircraft would be structurally fragile and in constant danger of breaking up in flight, especially in strong winds or when performing a violent manoeuvre such as pulling out of a steep dive. As airfields would be nonexistent, it’s landing gear would consist of fixed skids with bicycle type wheels (as designed by Sir George Cayley) but take off and landing would still be a perilous affair. The aircraft might well require some sort of portable catapult to help it get airborne.

With the success of the Navy’s airship program, the Army might once again be interested in such technology but this time under the control of the United States Army Signal Corps, commanded by Major Albert J. Myer. With a company of these new aerial scouts under his command, the Signal Corps would become the backbone of Army reconnaissance and intelligence in the field just as was the case in later years.

Armament

In the Civil War era, men envisioning aerial bombers were considered cranks rather than progressive forward thinkers ahead of their time. Though aerial scouts would be unable to carry anything in the way of armament, short of personal firearms for the pilot, airships would be quite capable of carrying a payload of 2 twinned Agar Guns (one each fore and aft) or a half-dozen bombs, 60-pdr rifled bursting shells with a drogue chute attached to insure they landed point down when released. Though such activity might be reserved for high value targets, this was not a new or unknown concept.

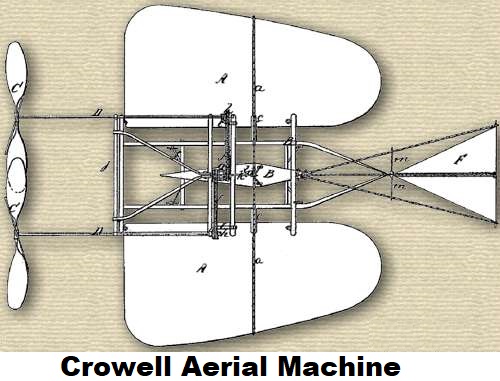

In June 1862 Luther C. Crowell of West Dennis, Mass., received a patent for a flying machine capable of carrying a bomb load. The sharp-edged hollow wings of the machine were designed to hold hydrogen gas, and with the power of a steam engine located in the cab, the wings were to pivot from a horizontal to a vertical position with dual contra-rotating propellers linked by chains or bands so that they could function both vertically and horizontally. This aerial bomber had a cone- or pyramid-shaped rudder, and the craft was designed to take off and land vertically. In February 1863 Charles Perley of New York City was awarded a patent for an unmanned aerial bomber similar to the balloon bombs used by Austria in 1849. Beginning on August 22 of that year the Austrians had launched some 200 pilotless balloons, each carrying 33 pounds of explosives, against the city of Venice, Italy, during an uprising there.

Usage

Just as would be the case in WWI, there would be some debate over the usefulness of aircraft in warfare and, as shown by the history of the Balloon Corps, many officers would remain sceptical. However Lee’s successful and stealthful withdrawal from Chancellorsville, leading to the Battle of Gettysburg, proved that cavalry could no longer provide the reconnaissance expected by their generals and it would be quickly realised that aircraft could at least locate the enemy, even if early air reconnaissance was hampered by the newness of the techniques involved. Airships, controlled by the Navy just as they controlled coastal and river Monitors, could be launched from balloon tenders and would be the perfect platform for long range or long duration reconnaissance, operating well above the effective range of any small arm or artillery piece that might be used against it. They could also carry a reasonable payload and generals would quickly come to realize that they could be used in the tactical bombing role a well as for scouting and reconnaissance. Following naval parlance, each airship would have a pilot, commander, signaller, engineer and engineer’s mate as well as an ordnance officer and ordnance crew if guns or bombs were carried.

Aeroplanes, on the other hand, would likely have a service ceiling of 18 ft in early models and perhaps twice that after some inevitable improvements are made and so be in constant danger from rifle fire that could easily reach out some 800 yards with accuracy. Poor rudder and lateral control would also make the aeroplane difficult and slow to turn and an easy target for sharpshooters. This and the fact that they had no capability to carry any sort of payload would eliminate offensive uses such as dropping small bomblets or firing on ground targets and their restricted range would relegate them to simple scouting rather than long range reconnaissance. To avoid having to land unnecessarily, messages quickly written by the pilot could be dropped in message canisters trailing long ribbons, as was done in the early years of WWI. These limitations would be systemic until the steam power plants of these aircraft could be replaced by more powerful internal combustion engines that wouldn’t become available until the turn of the century.